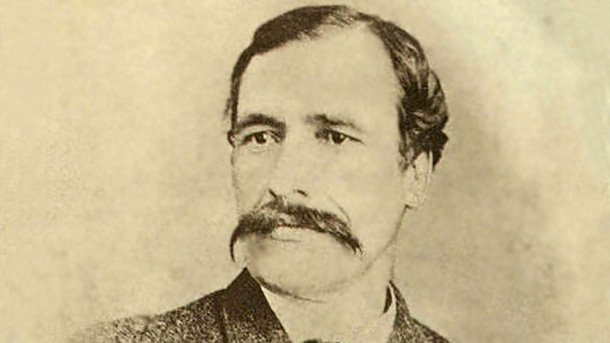

On 9 October Bulgaria marks the 145th death anniversary of Georgi Rakovski, an ideologist and founder of the organized Bulgarian national-liberation movement against the five-century Ottoman rule. “A passionate dreamer, an impossible man”: with this popular phrase the classic of Bulgarian literature Ivan Vazov characterized Rakovski in his brilliant poem of the same name. His life, quite generous in ups and downs, adventure and persecution, would be worthy of a thick Alexander Dumas novel. Rakovski was chosen by fortune to be the first in a handful of spheres. Few are aware, for instance, that he was the first to suggest a tricolour to serve as the Bulgarian flag.

Rakovski was born in 1821 in the town of Kotel in the Eastern Balkan Range, to a family of well-off merchants. His name by birth was Sabi Stoykov Popovich. He graduated from a prestigious Greek school in Istanbul where he studied natural science, liberal arts, ancient and modern languages. Starting in the early 1840s he joined various rebel acts of Bulgarians against the Ottoman Empire. In 1842 in Romania, he joined the Braila mutinies that had to do with the attempts of the Bulgarian emigrants to send over armed units to enslaved Bulgaria. However, since Romania feared a possible worsening of relations with the Empire, it sent troops to crush the Bulgarian mutinies. As organizer of one of the conspiracies, Rakovski was given a death sentence. As a Greek subject that he was at that time however, he was handed over to Greece and in the meantime, succeeded in fleeing to France. He spent roughly a year and a half in Marseille and returned to Bulgaria with the nickname Rakovski. In 1844 he was thrown in jail in Istanbul in the wake of a major row that he had with the Kotel’s dignitaries who were loyal to the Ottoman authority. He was released three years later.

In 1856 the start was given to the Crimean War waged initially between Russia and Turkey. Georgi Rakovski saw the war as a chance for Bulgaria’s liberation. In the meantime he was part of the organization of a clandestine society aimed to collect military information in support of Russia’s intelligence and to prepare the Bulgarians for an uprising. Rakovski succeeded in becoming chief interpreter of Turkey’s Danube Army but was soon disclosed as a Russian agent. He was arrested and had to face the death sentence for the second time, but fled once again. He quickly summoned a small armed unit in the Balkan Range and was bracing for new rebellious acts hoping on a strong Russian offensive. However it failed to happen, as both Britain and France intervened into the Crimean War.

In the wake of the Crimean War, Georgi Rakovski worked out a plan for the liberation of Bulgaria based on a nationwide uprising prepared in tune with the liberation struggles of other Balkan nations. For the purpose he got acquainted with the experience of Italian and Polish revolutionaries. In 1862 in Belgrade, Rakovski organized the First Bulgarian Legion, a 600-strong unit that had to enter Bulgaria and cause an uprising. This took place two years after the celebrated Garibaldi march with its 1000 volunteers. On 5 June 1862 a conflict broke out between Serbia and the Ottoman garrison in Belgrade at a time when Serbia was still vassal to the Empire. The Bulgarian legion demonstrated remarkable valour in combat and foreign diplomats and correspondents reported about it. However the Serbo-Turkish conflict was resolved and the Bulgarian legion was disbanded. During the years that followed Rakovski was given to diplomatic activity in the role of a mediator between the Balkan nations for the sake of joint actions against the Empire.

While committed to revolutionary and diplomatic work, Georgi Rakovski worked actively as a writer and journalist. He published a few newspapers. One of them, Dunavski Lebed (Danube Swan) was bilingual – in Bulgarian and French. He worked on some analytical articles that advocated Bulgaria’s democratic and European development. Some of Rakovski’s ideas came ahead of his time like for example for the cooperation among Balkan nations, as well as for ways to overcome differences between the basic Christian denominations – the Orthodox, the Catholic and the Protestant Church. He was also the founder of the Romantic wing in the modern Bulgarian literature. Similar to other Renaissance figures, Rakovski was in the know of several foreign languages and had truly encyclopaedic interests – from Bulgarian folklore to India studies that he himself pioneered in Bulgaria.

One of his descendants recounts that the Rakovski family had a blood relation with the last Bulgarian tsar before Bulgaria was conquered by the Ottoman Empire, Ivan Shishman. In Southeast Europe the Kotel genius was known as a Bulgarian prince. Though he was never secure financially, he had great self-confidence that he demonstrated in communication with the royals that off and on he met with.

In 1867 in Bucharest Georgi Rakovski was once again involved in preparing a liberation action – a few armed units (detachments) had to penetrate the Bulgarian lands. As work on the campaign peaked, Rakovski’s health deteriorated and he died of tuberculosis on 9 October, eleven years before Bulgaria’s liberation to which he had dedicated all his adult life.

Translated by Daniela Konstantinova

По публикацията работи: Veneta Pavlova

Последвайте ни и в

Google News Showcase, за да научите най-важното от деня!