This new series is bringing you a few shiny, brilliant bits from modern Bulgarian literature. It has been written for presentation to absolute beginners. The introductory installment provides a relevant background of the stories to come.

* * *

Bulgaria is a central Balkan country bordering on the Black Sea to the East and on the Danube to the North; a country often mistaken for other countries. The reason why could be that there are a few Bulgarias in history, and most emerged in different points of Western Asia. The most recent, however, was founded in 681 in the Balkans by a proud, civilized and militant tribe of Proto Bulgarians who most probably had Persian roots. They mixed with local Slavs and other ethnicities and created a powerful kingdom that both borrowed from and warred with mighty Byzantium, formerly the Eastern Roman Empire. I regret to say, Bulgaria was much more powerful and a European big power back in the Middle Ages. It adopted Orthodox Christianity in the 9 century and began using its own written language for its books. So, Old Bulgarian was the first literary language that squeezed in among the holy tongues, Greek, Latin and Hebrew.

As early as the 13th century, Bulgaria’s anonymous artist who created the breathtaking frescoes in the Boyana Church near Sofia displayed a Renaissance style of painting, and then, oh, no, in 1396 the Ottoman Turks conquered the cultured land of Bulgarians. Well, most of Bulgaria’s wealth, its political class and leading clerics were destroyed rather brutally. The keyword was now survival, in both the physical and moral sense, and this had to go on for five long centuries. The old glory of the country was hidden away in remote monasteries, and the people lived in small village communities where they worked on farms. The national identity was blurred, many were forcefully converted to Islam, and the regal past of the land was almost completely forgotten.

Everything looked rather bleak but it seems that Christianity, folklore and hard work were enough to save Bulgaria, and so in the second half of the 18 century the National Revival began. This was the beginning of modern Bulgaria, and as part of it, of modern Bulgarian literature. But what was the mechanics?

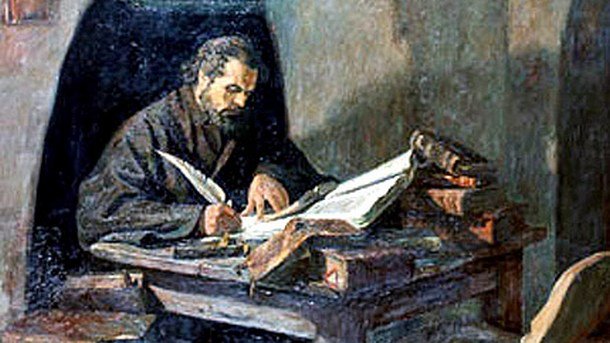

Simply, there was a humble man who wrote a thin brochure with the title Istoriya Slavyanobolgarskaya, A Slavo-Bulgarian History. Monk Paisy came in from the dark with the impossible task of persuading Bulgarians that they had had a glorious past. Now we don’t even know where he was born. A few towns and villages claim he was born there, keen to develop cultural tourism. What we know is that he had monastic schooling, spent sometime in Mount Athos and toured the Bulgarian lands to raise alms for the Hilandar Monastery. In the meantime this extraordinary man wrote his celebrated brochure, by the way a compilation of western writings about Bulgarian history, with little or zero value as a historical writing.

However, its foreword represents a brilliant pamphlet passionately urging Bulgarians to wake up, learn about their great history and take a path of liberation from both Greek influence and Turkish oppression. Paisy of Hilandar who has been canonized as saint by the Bulgarian church, was in fact the first great patriot and journalist in Bulgaria, absolutely self-made, and what he did was to go to villages and advertize his book. He urged locals to make written copies of it and via this media channel, the important message of the Bulgarian national identity reached out to various remote parts of the Bulgarian ethnic territory.

A FOREWORD TO THOSE WHO WOULD LIKE TO READ AND HEAR WHAT WAS WRITTEN IN THIS HISTORY

Excerpts, translation by Krasimir Kabakchiev (in the audio version)

"Be careful now, o you readers and hearers, o you Bulgarian people, who love your kinfolk and your Bulgarian fatherland and take them to heart and who wish to discover and understand what is known about the Bulgarian people, about your fathers, forefathers and kings, patriarchs and saints; how they lived and fared Throughout the whole Slavic world, the Bulgarians were the most glorious, they were the first to call themselves tsars, the first to have a patriarch, the first to be Christianized; they conquered the largest domain".

The thin brochure with the passionate foreword was a worthy start of the modern Bulgarian society. A few pages turned into the most powerful weapon for the national awakening of the land. All the way since then and until the 1980s literature was of paramount importance for Bulgaria’s public and political life. The land’s poets and writers have been among the most influential Bulgarians and a shamelessly large proportion of them have died violent deaths.

In future installments we will tell you more about the truly fascinating ups and downs of Bulgarian literature in this series that – rightfully enough - opens with the humble monk Paisy, who came in from the dark in 1762 to write and disseminate his extravagant history of Bulgaria.