St. George is one of the most venerated saints in Bulgaria. Sofia has three local saints who bear the same name, while Georgi is one of the most common names in this country. A great number of churches are dedicated to the warrior saint, killed because of his faith in 303 in Nicomedia, (today’s Izmit). Just 10 years after his martyrdom a profound change in the attitude towards Christianity took place. The Edict of Milan which promoted tolerance towards Christian was issued by Western Roman Emperor Constantine I, and Licinius, who controlled the Balkans. Actually the edict is a copy of a previous edict of tolerance from 311, issued by emperor Galerius from Serdica, today’s Sofia.

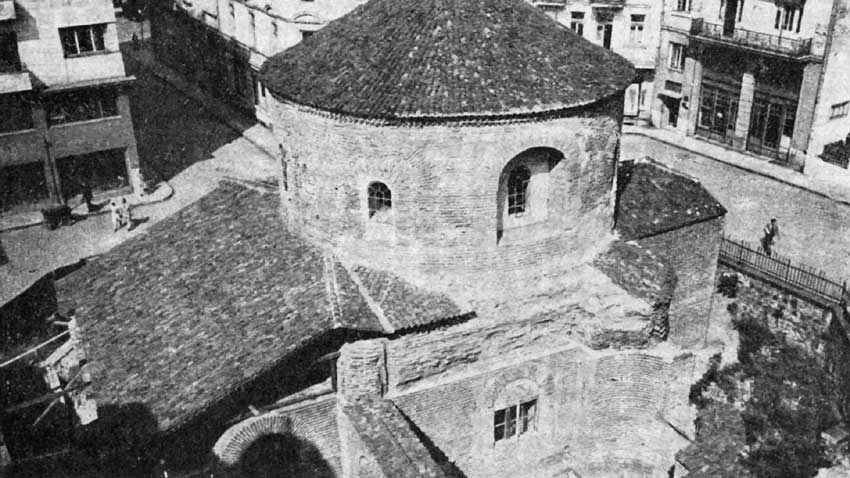

One of the oldest churches bearing the name of St. George is situated in this ancient city, in which Constantine the Great built a residence for himself. The church is known as the St. George Rotunda. It is the oldest well-preserved Roman building in Sofia, being a witness of the development of the city for nearly 1700 years. Since archaeologists started studying the rotunda it revealed a number of secrets to them, but there are unsolved mysteries too. One of the mysteries is related to the initial function of the building.

The St. George rotunda dates back to the beginning of the 4th century. The city was impressive back then with decorated marble facades of administrative buildings, spas, temples. These buildings were erected after 106 when Sofia became municipium. But during the time of Emperor Constantine construction relied mainly on bricks and the rotunda is a good example of the new architecture. The church was built on the foundations of older buildings, located in the administrative district of Serdica, known today as “Constantine’s neighborhood.” Next to the rotunda was the meeting room of the city council (buleuterion). Only the St. George rotunda remains today.

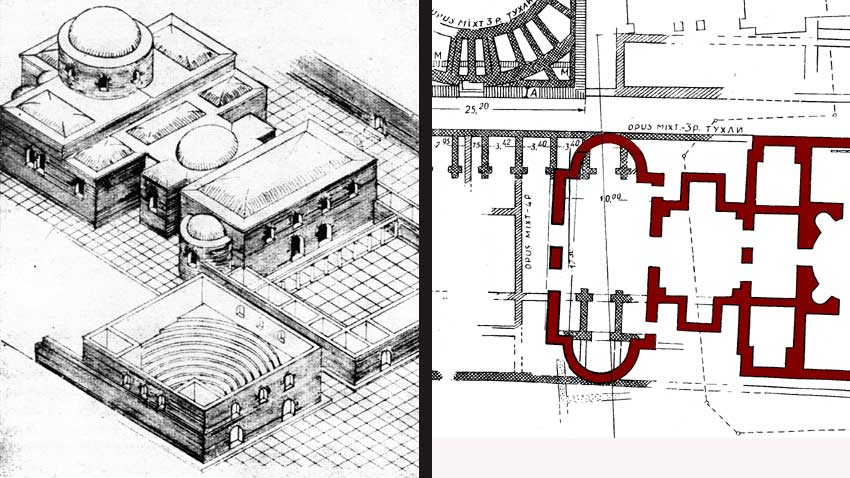

The scarce fragments of the ancient decoration of the rotunda do not tell archeologists enough about the initial function of the building. If we take a look at the plan we see its complexity. Walls are no thicker than 1.55 meters. The rooms of the building are lined along an east-west axis, similar to the rectangular street network. The oval room – the rotunda has a height of 14 meters and diameter of 9.50 meter. Light comes in through 8 windows and there is an apse to the east.

Renowned Bulgarian historian and archaeologist professor Bogdan Filov started studying the rotunda in the first decades of the 20th century. He published his results in 1933, claiming it was initially a Roman bath. Filov, however, was wrong because the conclusions were based only on partial archeological work. The rooms had underfloor heating called hypocaust, which used to be an indispensable part of Roman baths.

In 1939/40 more thorough studies started and it turned out that certain rooms necessary for a Roman bath were missing. What was previously thought to be a hypocaust turned out to be a construction to stop groundwater. Scientists also discovered that existing pools were not linked with the sewage system of the Roman city. What were they used for then? Turkish sources tell about a magic water spring that existed east of the rotunda. Some historians think the rotunda was the building where people could get access to the spring water. Buildings next to healing springs existed in Christian times too. The existing of a door in the apse to the east also backs the claim, as the door leads out and its existence in the altar room is unusual. Scientists say the door was used only during construction and then the opening was bricked up.

Others think the rotunda was dedicated to Christian martyrs (martyrion) and relics were ritually washed there. However, just some 50 years after it was built the rotunda started serving as a baptistery. The need for such buildings rose after the Roman Empire adopted Christianity in the end of the 4th century. A big hall was built next to the rotunda and previously existing basins were renovated. A change from martyrion to a baptistery seems unlikely which makes experts claim that the building served as a baptistery from the very beginning. However, the baptistery basin is not situated in the middle of the room as there are pools in the niches. This makes scientists doubt the claims that the building was a baptistery. It is also not known when and why the church started bearing the name of St. George.

Others think the rotunda was dedicated to Christian martyrs (martyrion) and relics were ritually washed there. However, just some 50 years after it was built the rotunda started serving as a baptistery. The need for such buildings rose after the Roman Empire adopted Christianity in the end of the 4th century. A big hall was built next to the rotunda and previously existing basins were renovated. A change from martyrion to a baptistery seems unlikely which makes experts claim that the building served as a baptistery from the very beginning. However, the baptistery basin is not situated in the middle of the room as there are pools in the niches. This makes scientists doubt the claims that the building was a baptistery. It is also not known when and why the church started bearing the name of St. George.

The vicissitudes of time affected the church. The building was used for less than 200 years. The dome and vaults of the other rooms fell down and the building was in ruins. Historians say this may have happened during the invasions of Huns and Goths in the end of the 4th century but most probably an earthquake like the one in 518 was responsible. In the 10th century when Serdica was already part of the First Bulgarian Empire the building was reconstructed as a temple. During the Ottoman rule the rotunda was turned into a mosque and after the Bulgarian state was restored, the building became a church once again. Today the rotunda is almost hidden between huge buildings from the period of Stalinism, but remains one of the architecture pearls of the Bulgarian capital city.

English version: Alexander Markov

Photos: BGNESThe Days of Croatian Archaeological Heritage, which will last until 8 November, begin today at the National Archaeological Institute with Museum at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (NAIM-BAS) in Sofia. The event is organised by the Croatian Embassy in..

Today, 6 November, marks 104 years since the annexation of the Western Outlands in 1920. Traditionally Bulgarian territories in south-eastern Serbia and northern Macedonia were ceded to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1920 as a result of..

Volunteers joined the efforts to clean and restore the monastery St. Spas near Bakadzhik peak. The campaign is being organized on 2 November by Stoimen Petrov, mayor of the nearby village of Chargan, the Bulgarian news agency BTA reports. The..

The Days of Croatian Archaeological Heritage, which will last until 8 November, begin today at the National Archaeological Institute with Museum at the..

+359 2 9336 661